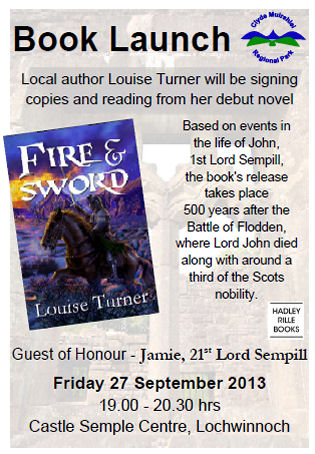

And now, it’s with great delight that I give to you the first of my blog posts devoted to ongoing archaeological work on medieval sites in and around Ayrshire and Renfrewshire. And one, indeed, which features in ‘Fire and Sword’, which is an added bonus!!

On Friday 13th September and Saturday 14th September, Ardrossan Castle Heritage Society have been undertaking a series of test pits across Castle Hill in Ardrossan, under the guidance of professional archaeologists from Rathmell Archaeology Ltd.

There’s an upstanding medieval castle on the site, which still survives in pretty good nick, despite having been subject to an artillery bombardment by Cromwell’s forces in the late 17th century.

During the late medieval period, Ardrossan Castle was in the possession of the Montgomeries, and in particular, the Lords Montgomerie (Later the Earls of Eglinton). So any works on going here are of particular interest to me, as it’s a site which has a strong connection with Hugh Montgomerie (2nd Lord Montgomerie, 1st Earl of Eglinton).

The test-pitting on Castle Hill has been carried out in order to try and evaluate the archaeological potential of the wider area around the upstanding ruins of the castle, examining in particular the possibility of there being remnants of a more widespread ‘castletoun’ in the vicinity, and also the place of this relatively late structure in the longer chronological narrative of the hill’s occupation.

While it’s difficult to draw any clear conclusions about structural remains and archaeological features when excavations are being carried out at this kind of level (it’s a bit like carrying out keyhole surgery, when you’re working in the dark and the species that you’re operating on is unknown), what these works have clearly proven is that there is archaeological potential on this hilltop.

I’m sure the star finds will be the tiny lithic scrapers which have been uncovered here, demonstrating occupation of the hill right back into the Bronze Age and perhaps earlier. But there’s been evidence dating to the medieval period, too, like this fragment of gritty pottery:-

This pottery type pre-dates the events of ‘Fire and Sword’, unfortunately. But never mind, it’s still good!

What’s all the more exciting is that these initial investigations are likely to be the start of larger explorations, undertaken as part of ongoing restoration works taking place both on the castle itself, and in its wider environs. To keep up with the latest news, why not ‘like’ the Ardrossan Castle Heritage Society’s Facebook page, on https://www.facebook.com/pages/Ardrossan-Castle-Heritage-Society/375807702480483?hc_location=stream